Silsila - Maldives Pavilion

La Biennale di Venezia / 55th Venice Biennale

1st June - 24th November, 2013

Curators: CPS – Chamber of Public Secrets; Alfredo Cramerotti, Aida Eltorie, Khaled Ramadan

Artist page on Maldives Pavilion website

Silsila

Silsila — Arabic for ‘chain’ or ‘link’— is a site-specific video installation work that depicts Alshaibi’s three-year cyclic journey through the significant deserts and endangered water sources of the Middle East and North African region and across to the bountiful waters of the Maldives. By linking the performances in the deserts and waters of the historically Islamic world with the nomadic traditions of the region, and the travel journals of the great 14th century Eastern explorer, Ibn Battuta, Alshaibi seeks to unearth a story of continuity within the context of a threatened future. Silsila takes its inspiration from the Sufi poet Assadi Ali, who began each line of his poems, “I, the Desert.” An excerpt from that poem calls for us to recognize our common identity: “the grains of my sand rush in asking/begging You [Allah] to keep my descendants / and nation united.” Silsila is a story of shared history and soon-to-be-written future — the tales of the climate refugee and its geographic voice and our search for connection with each other as interdependent peoples and nations plagued by an unthinkable future.

Alshaibi’s Silsila: Invoking Routes Across Sand and Sea

Author: M. Neelika Jayawardane

When I first invited Sama to my flat in Denver, Colorado, I made pani walalu – bangles of honey – to welcome a sister into my home. When she arrived, I was squeezing the runny dough into hot coconut oil through a small circular nozzle attached to a French pastry tube (my diasporic innovation on tradition). Sama arrived in time to eye the concentric circles, puffing up golden and rising to the top of the oil. I dipped each bangle into cardamom-infused sugar syrup, and we ate them hot. When she tasted her first pani walalu, she knew exactly what it was: ‘Oh, zalabiyah. That’s what you made.’

What Sama and I had immediately was an easy alliance that comes with the knowledge of migration, displacement and otherness. She: a recently naturalized American of Iraqi-Palestinian origins; I: very much a foreigner teetering on the edge of legality in the U.S. on my dubious Sri Lankan passport (one that still permits me little access through any border). saw in her a fellow traveler who understood the aesthetics of longing: of realigning self with ideal possibilities, of fashioning allegiances beyond expediencies, geographic boundaries and political borders. We both laughed knowingly about the impossibility of answering the ubiquitous question that greeted us every day in places like Colorado: ‘Where are you from?’ Sama can tell you that there was never one answer for that question. An inquiry about origins is often innocent, but it is also a question asked of the perceived other at security checkpoints, by border-keepers. It demands an easy origin, a pinpoint, and a reference through which the inquirer can easily package the supplicant at the border. The discomfort that it produced in both of us, and the impossibility of answering that question, as well as the frustration of always playing the translator, the historian, the patient educator led us to find different ways to respond. It was the source of Sama’s art, and of my writing.

Video documentation at Maldives Pavilion.

Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery

Music composed by Grey Filastine,

featuring Brent Arnold (cello) and Abdel Hak (violin)

Pani walalu journeyed far and wide along the borders of the Indian Ocean world, across land and sea routes. They are believed to have originated in northern India; the oldest known recipe is recorded by the Jains, who called them jellebi. They were transported westward after the arrival of Muslim rulers who conquered most of India for several hundred years. The many variations in their name tells us about their journey: in Pashto, they are źəlobəi; in Persian, zulbia; in Arabic, zalabiyah. When they are arrived in North Africa, they took on a new life as zalabiya in Egypt, and in the Maghrebi countries of Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, they became zlebia. When they returned towards origins via sea route, they carried their Arabic intonations: in the Maldives, they are known as zilēbi. The Sri Lankan Sinhalese – island neighbor to the Maldives – abandoned all custom, and called them by a picturesque name: rich as the golden bangles honey-dripping from a bride’s arm. Long before us, there were adventurers, traders, rulers and slaves who moved between the water-parched lands in which Sama began her life, and those waterlogged archipelagos on which my people made life. We don’t really know whom first fried concentric circles of runny dough in oil, then dipped them hot into honey, but we know that the trade routes first documented by Ibn Battuta transported them from port to port. The tri-cornered lateen sail of the dhow, the monsoon, and restlessness brought us together. We became part of each other through contents of the cargo-holds of these time travelers, and the curvature of their backbones gave shape to our many storied journeys. We each thought that the architecture of a temple, or the practice of removing shoes at the doorstep, or a recipe for a delicacy was ‘ours’, only to discover that our cousins in faraway places did the same. Each part of us embodied the memory of trades we made centuries ago: the shape of our eyes, the length of our eyelashes, the curvature of our noses, the curl of our hair, the rippling shades of our skin. We tasted each other. We consumed each other.

At the Maldives Pavilion, each part of Alshaibi’s multimedia installation, Silsila, alludes to those powerful historic linkages. Through her installation, we remember that we share deeper topographies of memory; we see intimations of worlds established not by rulers and the networks of power they sought to establish, but by waves of longing, desire, adventure, curiosity, need, and hope.

In much of her previous work, Alshaibi focuses our attention on the artificiality of borders – barriers meant to eliminate porousness, to prevent knowledge, aesthetics, and bodies passing through. In Venice, Alshaibi shifts her focus towards possibilities for constructing a life outside of border restrictions, a freedom inspired by the epic travelogue of the 14th century explorer Ibn Battuta. The elements Alshaibi positions in a room with vellum-like textured walls suggest time-travel: the building reminds us of the continuing presence of the past, while her video work is housed in smooth black boxes mounted on the walls of the room, and the light boxes positioned on the floor are the futurist-present part of this journey. The great curvature of a modified Maldivian dhoni’s keel – positioned upside down, 5m long, 2.5m tall, 11.5cm wide – dominates the room. It is the spine and strength, providing shelter to the hopes outlined in the three light boxes; it is the backbone visitors must walk under in order to get to the video portals. The balsa wood that Alshaibi chose for the keel makes it appear more like bone, alluding to disuse and death; yet it is also an archway that connects history with the present – a time traveler on which we can journey from past to present and back.

Alshaibi names her installation Silsila – Arabic for ‘chain’ or ‘link’ – signifying the historical and spiritual linkages between deserts and endangered water sources of North Africa and the Middle East, and the water-abundant rim of the Indian Ocean world. To film part of the footage, Alshaibi once traveled seven days in the summer desert; she realized that it ‘forced me to think of fear as an asset (because I had to pay attention in order to live), and a force to overcome (so that I could gear up the willpower to continue to work in such situations).’ The danger inherent in inhospitable spaces is what attracts Alshaibi; for her, surviving and working within these landscapes inspires her to be mindful of breath and life, to remain reverent of powerful natural entities beyond human control. In her work, the desert and the ocean are protagonists; both are near impenetrable, permitting only vigilant travelers a way through. But always, the desert and the ocean remind us: they are in charge of our survival. Inevitably, Alshaibi’s focus is on the impenetrability of power, as well as the ways in which people circumnavigate those impenetrabilities.

Each of the jet-black plexi boxes hung on the wall house video montages, taken on her travels through these regions – titled ‘Dhikr,’ ‘Baraka,’ ‘Muraqaba,’ respectively – that only one person can view at a time. The viewer will see her or his own eyes, and video that appear to be floating. The figure in the videos (performed by Alshaibi) journeys through desert and waterscapes, creating an ephemeral path – an open invitation – for those who wish to follow. There is no sound produced by the video; but the music – created by the sound artist Filastine, with whom Alshaibi collaborated – is part of the room, accompanying the viewer through each visual journey. Alshaibi explains that these viewing portals ‘act like tombs or tunnels; they are akin to the holy Kaaba in that they are personal spaces for self reflection.’ During these intimate communions, one feels still, transported to a state of meditation. Beneath the spine of the stylized keel of the dhoni, there are three custom-made wooden boxes, lined up next to each other. Two are light boxes: one is an etching on glass, depicting Ibn Battuta’s first epic journey; the second is an etching tracing Ibn Battuta’s second route. The routes are abstracted outlines, void of land or water boundaries, cities or national borders. Because those landscapes are now vanished, we only have projected fantasies through which we can meditate on those passages. The juxtaposition of the video and the etched routes allude to the conflict between knowing and unknowing: one suggests deep, embodied knowledge of Batutta’s experiences – albeit colored by romanticized, ‘exotic’ fascinations– whilst the other indicates that the material evidence of his travels reveals little.

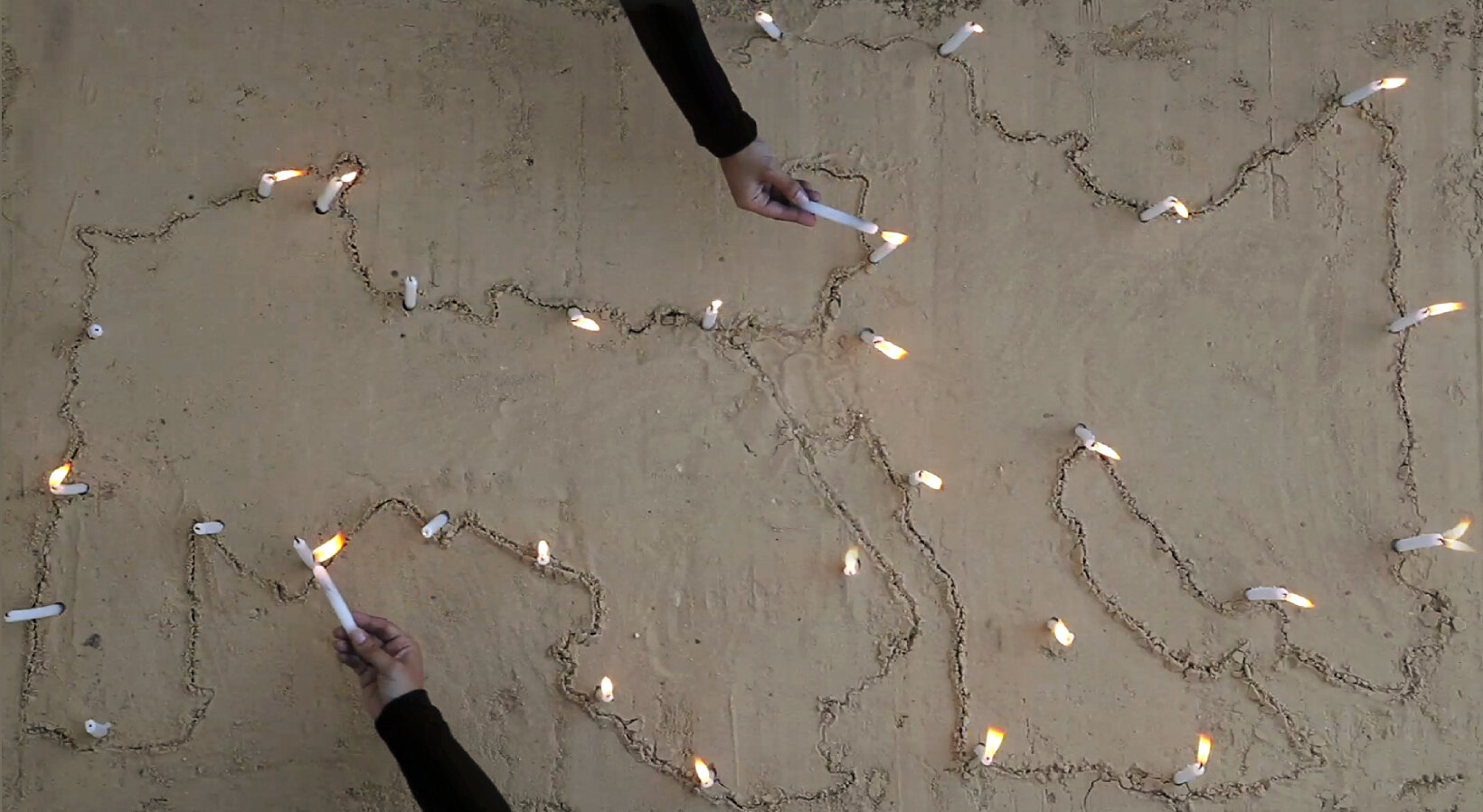

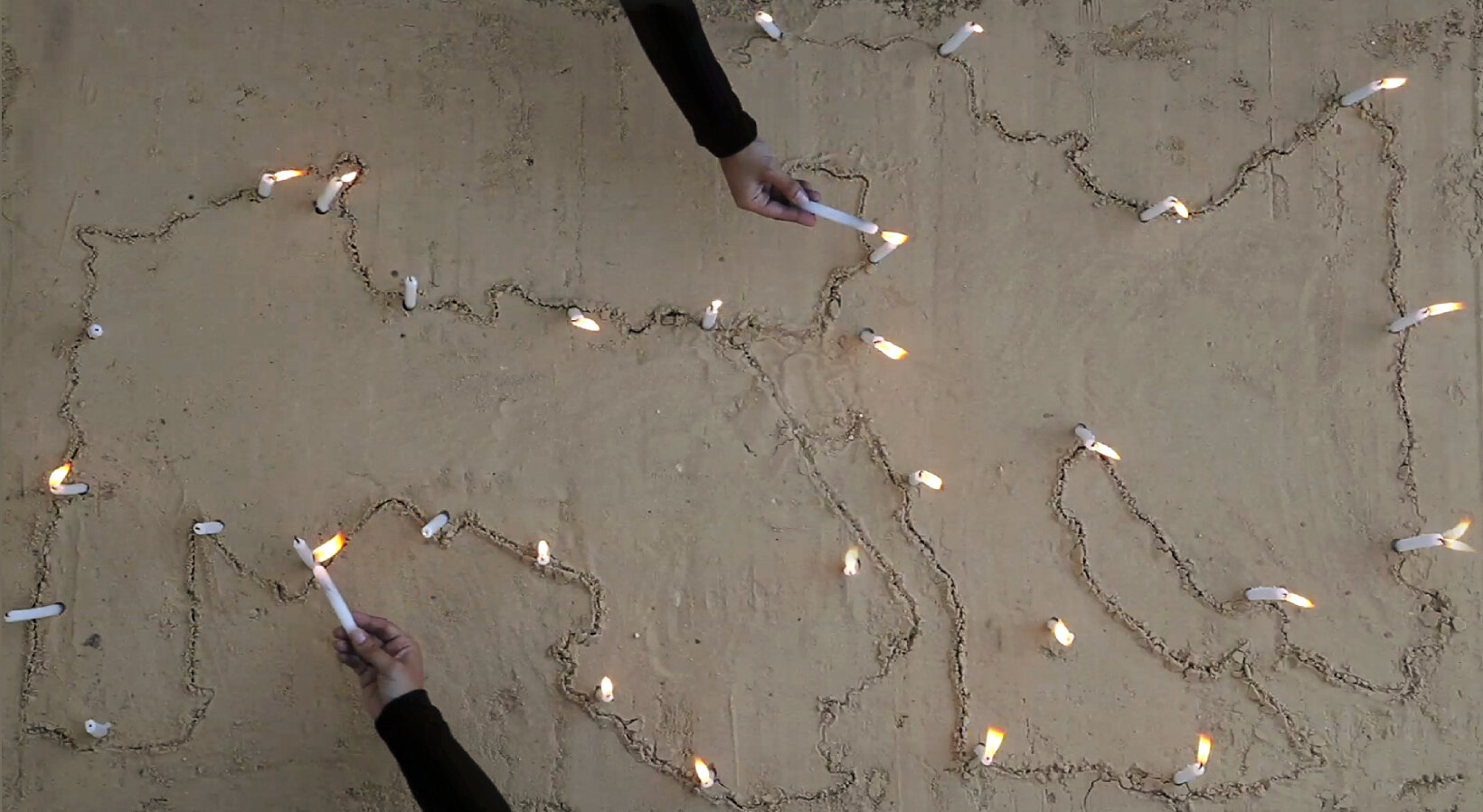

In the middle of these two light boxes, a custom-made box houses the video ‘Noor’: we see a outline of the territory that we know today as the Middle East and North Africa, carved into sand. Again, no national borders are specified. Hands reach in, light candles along the outer boundary. The hands tend to the flames, attempting to keep the flames of his journey alive. Feathers fall from above, and cover the map. Some feathers burn, some fly away, some remain. The map turns into fractured mosaic forms, circles into spinning colors, and disappears. Whilst the mystical and historic significance of Batutta’s journeys through inhospitable landscapes are a reminder of the fragility of human ideals, of struggle, and our ever-present journey towards death, the chains of conversations establishing lineages – between ancient traveler and modern seeker, between host and traveler, between the ever-changing thread of skin that plays at the edge of water and sea – are kept alive. Through alluding to Ibn Battuta’s great leaps of faith across desert and ocean, Alshaibi reminds us about the heightened sense of connection – with Creator, Self, Otherness– that comes when one becomes mindful.

But we remember that Battuta’s travelogue also illustrated the limits of one’s ability to fully accept difference and otherness, despite all one experiences. In the Maldives, he was shocked to see that women went about uncovered above the waist; and even more shocked that the authorities who hired him as qazi weren’t that interested in enforcing rules. He writes, bemused by such lackadaisical island morality: The women of these islands do not cover their heads, nor does their queen…Most of them wear only a waist-wrapper, which covers them from their waist to the lowest part, but the remainder of their body remains uncovered. Thus, they walk about in the bazaars and elsewhere. Nakedness is one of the primary ways in which we mark the savagery of the other. And Battuta’s journeys, which expanded the borders of his – and our – understanding about how to be in the world, were not always able to open portals of understanding.

Driven by the impending disappearance of the island nation, the Maldives Pavilion’s curators chose to think of nation as a network of ideas, aesthetics, and dreaming: of possibilities far more viable than vying for short-term power. Their theme, ‘Portable Nation,’ implies uncertainty in the geographic and political future of the nation state as sea levels rise and threaten to vanish the archipelago of islands by 2080. As such, they chose artists whose work is more interested in exploring relationships built on collaborative networks. Sama Alshaibi’s work reminds us about the historical traditions that continue to link peoples across land and sea in this region. She takes her inspiration from the Sufi poet Assadi Ali, who reminded us to recognize our common identity in the face of annihilation and disappearance: ‘the grains of my sand rush in asking / begging You [Allah] to keep my descendants/and nation united.’